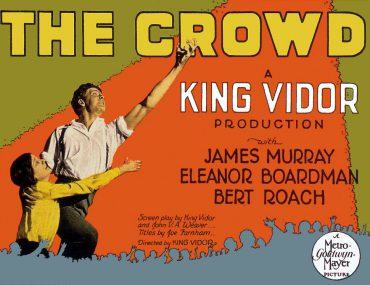

THE CROWD

(La folla)

King Vidor (US 1928)

Score: Carl Davis (Thames Television; Faber Music Ltd.)

Performed live by: Orchestra San Marco, Pordenone

Conductor: Carl Davis

“I made pictures as a good employee and pictures that came out of my own insides. This is one that came out of my guts. There was a lot of hypocrisy in early films and I wanted to get away from it,” King Vidor said in a 1978 interview. The Crowd broke every rule in the book and was so offbeat that Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer delayed it for almost a year. It was dismissed in some circles as an “artistic flop” but earned Vidor the first of five Academy Award nominations as Best Director.

A native of Galveston, Texas, who made his way to Hollywood in 1915, King Vidor worked as an extra for $1.50 a day to get his foot in the door. A decade later, The Big Parade would win both Vidor and M-G-M widespread acclaim. The unexpected success of the film – which earned the studio its biggest profit until Gone With the Wind – resulted in an unprecedented opportunity.

Vidor pitched Irving Thalberg a film about the average man walking through life, and the drama taking place around him. All too aware that audiences wanted escapism and not the harsh realities of existence, the director warned Thalberg that such a story “may not pack the theaters as much as we hope.” However, the producer assured Vidor that M-G-M could “afford an experimental film every once in a while,” and approved the project without seeing a script.

In his autobiography, Vidor recalled that he and Harry Behn, who wrote the screenplay for The Big Parade, “simply listed the important things that happen to the average man.” Vidor apparently then gave the list to playwright-poet-novelist John V. A. Weaver, or sat for a similar session with him.

The Clerk Story, a 49-page scenario written by Weaver early in 1926, is much like the film in some aspects, substantially different in others. Frank and Sue are easily recognizable as the film’s John and Mary. The most significant difference is the presence of Arthur, Frank’s romantic rival, a prominent character who disappears from later versions of the story.

The director himself took the second pass at getting his epic down on paper, in a 14-page treatment written in October 1926. Dubbed March of Life, the script outlines a film much more recognizable than the original scenario. Weaver, however, ended up getting co-screenplay credit with Vidor.

The final screenplay, by King Vidor and Harry Behn, is an artful marriage of Weaver’s The Clerk Story and Vidor’s March of Life. Now titled The Mob, this script yields a number of surprises. The most startling is a major supporting character, John’s childhood sweetheart Colette, who eventually tries to seduce him. (Portrayed by M-G-M contract player Dorothy Sebastian, soon to appear in Our Dancing Daughters, Colette’s role would end up entirely on the cutting room floor.)

Vidor sought an unknown actor for the lead, feeling “the film would carry much more conviction.” He found James Murray working as an extra at M-G-M; the actor didn’t believe him when Vidor said he might have a job for him, and had to be paid a day’s wages to make a screen test. Eleanor Boardman, who began her career with Goldwyn in 1922 and became Vidor’s second wife, was pregnant with her first child when she shot the honeymoon sequence on location in Niagara Falls. Most worrisome were the Coney Island scenes involving the fast-moving amusement park rides, which she did without a stunt double.

The primary visual influence on The Crowd, photographed by Henry Sharp (cameraman on Fairbanks’ Technicolor swashbuckler The Black Pirate), was provided by the likes of F. W. Murnau and Fritz Lang. In addition to the celebrated skyscraper shot early in the film, German Expressionism also influenced the scene where the boy climbs the staircase, and the hospital sequence when Mrs. Sims gives birth.

The film officially went into production on 23 December 1926, and completed studio filming on 12 March 1927. Vidor traveled to New York in May and continued shooting on location into June, including the Niagara Falls sequence. He filmed his amusement park scenes not at Brooklyn’s iconic Coney Island fun zone but at Abbot Kinney Pier in Venice, California; The Crowd was one of the first films to use New York City extensively as a filming location, however.

So nervous were M-G-M executives about the film’s unorthodox finale that a total of seven endings were written. The studio’s preference, with the family celebrating Christmas, ends with John telling Mary, “You’re the most beautiful girl in all the world,” and Mary assuring him, “I never lost faith in you for a minute.” The film was clumsily sent out to theatre owners with the alternate happy ending and the choice left up to them, though it was rarely if ever shown.

Four months after The Jazz Singer sounded the death knell for the silent era, The Crowd opened, on 18 February 1928, at the majestic Capitol Theatre in Manhattan, where James Murray once worked as a doorman. Film Daily enthused, “it’s so true to life… it clutches the heart, dims the eye and plays on every emotion.” The New York American felt it belonged on the list of the year’s ten best pictures. Yet Variety flatly called it “a drab actionless story of ungodly length.”

The film was nominated for an Academy Award for “best artistic quality of production.” M-G-M’s Louis B. Mayer himself voted against the movie for the big award because it dared to show the bathroom in the family apartment, calling it “that goddamn toilet picture.”

The Crowd’s innovative visual concept of the office inspired or foreshadowed similar scenes in many other films, including Yasujiro Ozu’s Tokyo Chorus, Preston Sturges’ Christmas in July, Billy Wilder’s The Apartment, Orson Welles’ The Trial, Jacques Tati’s Playtime, and the TV series Mad Men. Vittorio De Sica told Vidor The Crowd inspired him in making Bicycle Thieves.

Jordan R. Young

The Crowd and I: The music

Scoring The Crowd in 1981 followed the extraordinary premiere of Napoleon in 1980 at the London Film Festival. That event provoked a reaction from a newly formed TV channel, Channel 4, to commission a series of silent film classics to be restored and rescored by Kevin Brownlow, David Gill and myself, the team that had just completed a unique 13-part series, Hollywood. The Crowd was the first of many “silents” that I scored for Channel 4 and have continued to do, creating a repertoire now performed globally.

Napoleon was a vast historical epic, now running over 5 ½ hours in its present cut. Its score was centred around the music of Beethoven, Haydn, and Mozart. The Crowd couldn’t be more different. Made in 1928, it is also set in 1928. Instead of minuets and gavottes, we hear the Charleston, foxtrots, and the Blues. Its characters are not generals, kings, and revolutionaries, but ordinary folk struggling with everyday matters – but that does not make their lives any less important and at times heroic.

To solve the “heroic” side of the lives of our central couple, a classical, operatic tone is set, recalling a verismo opera of the late 19th and early 20th century. I am now remembering a Napoleon French review, calling it “un opéra sans voix”. But contemporary life intrudes. After all, the 1920s was the Jazz Age. From within the symphony orchestra I drew a jazz ensemble with, typically, a clarinet, saxophone, trumpet, and trombone, adding a rhythm section, piano, guitar (sometimes playing ukulele), drums, a solo violin, and a string bass. The large orchestra and the jazz ensemble at first alternate, and then finally combine. The hero of the film was in born in 1900. He would be in his 20s in the 1920s, and that’s where we find and leave him.

Carl Davis

Maggiori informazioni sul film in/More information about the film can be found in: Jordan R. Young, King Vidor’s “The Crowd”: The Making of a Silent Classic. Research associate: Kevin Brownlow. Past Time Publishing Co., 2014.

Durante le Giornate, alcune copie del libro saranno disponibili presso lo stand di FilmFair. / During the Giornate, some copies will be available at the FilmFair.

scen: King Vidor, John V.A. Weaver, [Harry Behn].

did/titles: Joe Farnham.

photog: Henry Sharp, [John Arnold].

mont/ed: Hugh Wynn.

scg/des: Cedric Gibbons, Arnold Gillespie.

cost: André-Ani.

asst dir: David Howard.

cast: Eleanor Boardman (Mary Sims), James Murray (John Sims), Bert Roach (Bert, il collega/John’s co-worker), Estelle Clark (Jane, la sua ragazza/Bert’s girlfriend), Daniel G. Tomlinson (Jim, fratello di Mary/Mary’s brother), Dell Henderson (Dick, l’altro fratello/Mary’s brother), Lucy Beaumont (madre di Mary/Mother), Freddie Burke Frederick (il figlio/Junior), Alice Mildred Puter (la figlia/daughter), [non accreditati/uncredited cast: Johnny Downs (John Sims, 12), Sally Eilers (brunetta alla festa/brunette party girl at Bert’s place), Sidney Bracey (capo ufficio/Sim’s office supervisor), Virginia Sale (vicina comprensiva/sympathetic neighbor), Warner Richmond (il padre di John/Mr. Sims, John’s father), Anne Schaefer, Larry Steers, Joseph Girard, Claude Payton].

prod: Irving Thalberg, M-G-M; prod.

mgr: George Noffka; unit mgr: Jack Cummings; prod. supv: J.J. Cohn.

dist: M-G-M. uscita/rel: 18.02.1928.

copia/copy: 35mm, 8399 ft., 104′ (20-22 fps); did./titles: ENG.

fonte/source: Photoplay Productions, London.

Italiano

Italiano