THE LAST OF THE MOHICANS

Maurice Tourneur, Clarence L. Brown (US 1920)

Maurice Tourneur, having left France in 1914 and set up a studio at Fort Lee, New Jersey, had created a reputation as a great pictorialist. Critics hailed him as “the poet of the screen”, referring to him in the same breath as D. W. Griffith. Like that great director, he had surrounded himself with a crew of devoted and highly talented colleagues. But recently he had had to replace some of his best men.

His first assistant director remained loyal: a former automobile mechanic called Clarence Brown. “Tourneur was my god. I owe him everything I’ve got in the world. If it hadn’t been for him, I’d still be fixing automobiles.”

Tourneur, who hated shooting exteriors, tended to hand them to his capable assistant, who also learned from him the crucial art of editing. In 1919, Tourneur encouraged Brown to direct his first feature, The Great Redeemer, which would be photographed by Charles Van Enger.

In July 1920, Tourneur helped to form Associated Producers with such figures as Thomas Ince, Allan Dwan, Mack Sennett, and Marshall Neilan. The whole enterprise depended upon The Last of the Mohicans, their first picture. Two weeks into production, according to Brown, Tourneur fell off a wooden camera parallel and was in bed for three months. Understandably, this potential disaster was not reported to the press, and when a brief paragraph did appear, it reported that Tourneur was suffering from pleurisy. Cameraman Charles Van Enger, interviewed in the 1970s, had no memory of the accident. Jacques Tourneur remembered his father with pleurisy; he thought Brown might have shot 30% of the film. However, Van Enger told me in 1969 50%, and Richard Koszarski in 1973 90%. Either way, Tourneur generously ensured that Brown got a co-directing credit, which gave his career a tremendous boost.

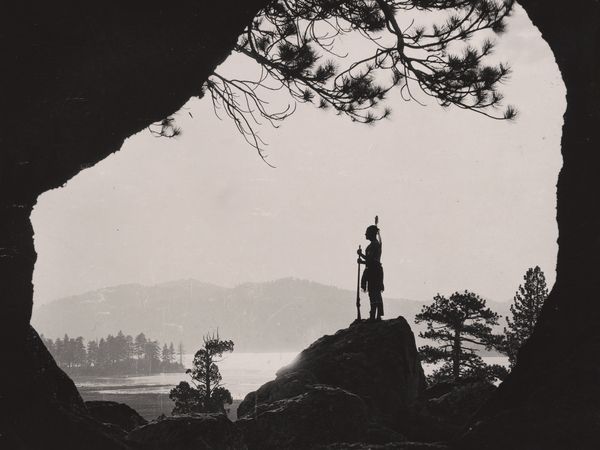

“I made the whole picture after that,” said Brown. “We made it at Big Bear Lake and Yosemite Valley. I had learned by this time never to shoot an exterior between 10 a.m. and 3 p.m. The lousiest photography you can get is around high noon when the sun’s directly overhead.”

The crew had to get up at 4 a.m. They made much use of lighting effects and weather atmosphere, using smoke pots to create sunrays striking through woodland mist. A rainstorm in the forest was supplied by a fire engine. Orthochromatic film was insensitive to blue, but Brown ensured he got clouds by using filters and the new, extra-sensitive panchromatic film. Van Enger claimed in 1969 that this was the first feature to use panchromatic.

Said Brown, “When the girls are escaping from the Indian ambush, I put the camera on a perambulator. We built it from a Ford axle, with Ford wheels, a platform and a handle to pull it down the road. We follow the girls running away; suddenly two Indians block their path. The camera stops – the perambulator stops – and this accentuates the girls’ surprise.”

Although Al Roscoe’s father was half-Indian, no full-blooded Native Americans appeared. (“To hear the assistant director call up our Indian extras in the morning was like calling a roll-call of the world,” said Brown.) This lack of authenticity brought the film a degree of criticism in the 1970s, even though Indian roles were still being filled then by the likes of Dustin Hoffman. (Boris Karloff is often credited with a role as an Indian, but when I asked him, he said: “Was I in that?”)

Eventually, Tourneur screened all the rushes. He could be very blunt. “The first raspberry I ever heard came from Maurice Tourneur,” said Brown, “and when I heard it I knew it meant a retake.”

Yet he felt it the equivalent of an Academy Award when Tourneur murmured “Not bad, Mr. Brown, not bad.” Tourneur was, however, critical of Barbara Bedford’s performance. She had only made one other picture – Tourneur’s Deep Waters (1920) – but Brown, who thought little of her as an actress, and treated her somewhat roughly, nevertheless coaxed from her a strong performance.

Tourneur’s brilliant art director, Ben Carré, had left the company, to be replaced by Floyd Mueller. A veteran of The Great Redeemer, Mueller confessed that the story gave him little scope for sets (apart from Fort Henry, built on the Universal backlot), and he was apathetic towards Indians. Tourneur subsequently fired him, replacing him with Sessue Hayakawa’s art director, Milton Menasco.

The Last of the Mohicans was a difficult production, and the company eventually ran out of money. The directors of Associated Producers attended a meeting at Universal City, where Brown told them the film would require another $25,000. When they saw a rough assembly, they voted him the money.

And the film did make money, even though a German version (with Bela Lugosi as the Indian hero) was imported to compete with it.

Photoplay thought so highly of the Tourneur film that it advocated that it be placed in a National Cinematographic Library, “for it treated an important subject with dignity without losing sight for an instant of its picture possibilities”.

When we were watching the film at the Cinémathèque Française in 1965, Brown said footage was missing from the end. It had been his task to keep the Indian and the white girl from touching each other, since miscegenation was subject to censorship, but the final shot had shown their hands coming closer and closer…

The Last of the Mohicans was the first major production in one of the most outstanding, yet overlooked careers in American cinema: Clarence Brown. Once he had graduated from Tourneur, he joined Universal and directed a group of superb dramas including Smouldering Fires (1925), and at M-G-M, no fewer than seven pictures starring Greta Garbo.

Brown never lost touch with his mentor. When Tourneur, now retired and living in France, was seriously injured in a traffic accident, Brown visited him whenever he could and put him on salary for the rest of his life.

Kevin Brownlow

regia/dir: Maurice Tourneur, Clarence L. Brown.

asst dir: Charles Dorian.

scen: Robert A. Dillon; dal romanzo di/based on the novel by James Fenimore Cooper (Boston, l826).

adapt: John Gilbert [non accreditato/uncredited].

photog: Philip Dubois [Tourneur], Charles Van Enger [Brown].

scg/des: Floyd Mueller.

mont/ed: Clarence Brown.

co. mgr: Robert B. McIntyre.

make-up, cost: Art Lee.

pubblicità/publicity: James B. Elliott.

locations: Yosemite (tra cui/including Nevada Falls, Vernal Falls, Overhanging Rock), Big Bear Lake, Lake Arrowhead.

cast: Wallace Beery (Magua), Barbara Bedford (Cora Munro), Al Roscoe (Uncas), Lillian Hall (Alice Munro), Henry Woodward (maggiore/Major Heyward), James Gordon (colonello/Colonel Munro), George Hackathorne (capitano/Captain Randolph), Nelson McDowell (David Gamut), Harry Lorraine (Hawkeye), Theodore Lorch (Chingachgook), Jack McDonald (Tamenund), Sydney Deane (generale/General Webb), Joseph Singleton; stuntman: Gene Perkins.

prod: Maurice Tourneur Productions.

dist: Associated Producers.

copia/copy: 35mm, 1560 m., 68′ (20 fps); did./titles: ENG

fonte/source: Eye Filmmuseum, printed in 1991 at Haghefilm Laboratories, from a nitrate print with Tchech intertitles, provided by the Narodni Filmovy Archiv and new English intertitles, courtesy of George Eastman Museum

Italiano

Italiano